What impact will COVID-19 have on the environment?

4 May 2020

COVID-19 has affected our daily lives in an unprecedented range of ways, from physical distancing to travel bans. But the pandemic is also influencing our planet.

Air pollution levels have dropped significantly since measures such as quarantines and shutdowns were put in place to contain COVID-19. Around the world, levels of harmful pollutants like NO2 (nitrogen dioxide), CO (carbon monoxide), SO2 (sulfur dioxide) and PM2.5 (small particulate matter) have plummeted—at least, while shutdowns continue.

But environmental benefits will only be temporary unless we implement long-term measures to cut emissions. It’s a stark reminder that air pollution, including greenhouse gas emissions, is a global threat that can’t be forgotten, even in these challenging times.

Global air pollution drops dramatically

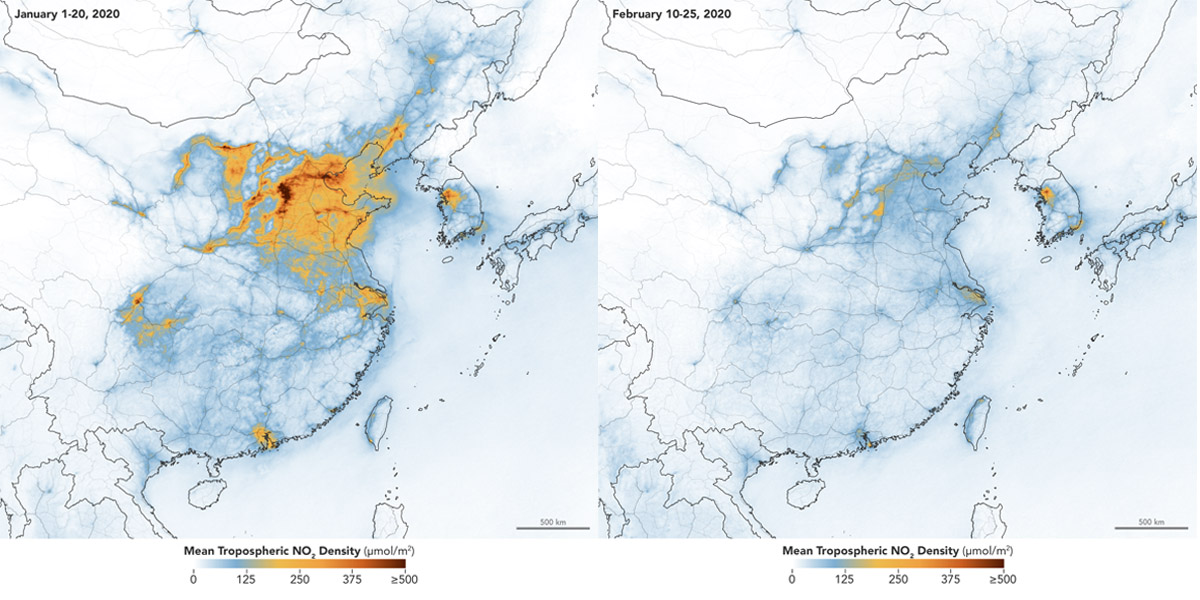

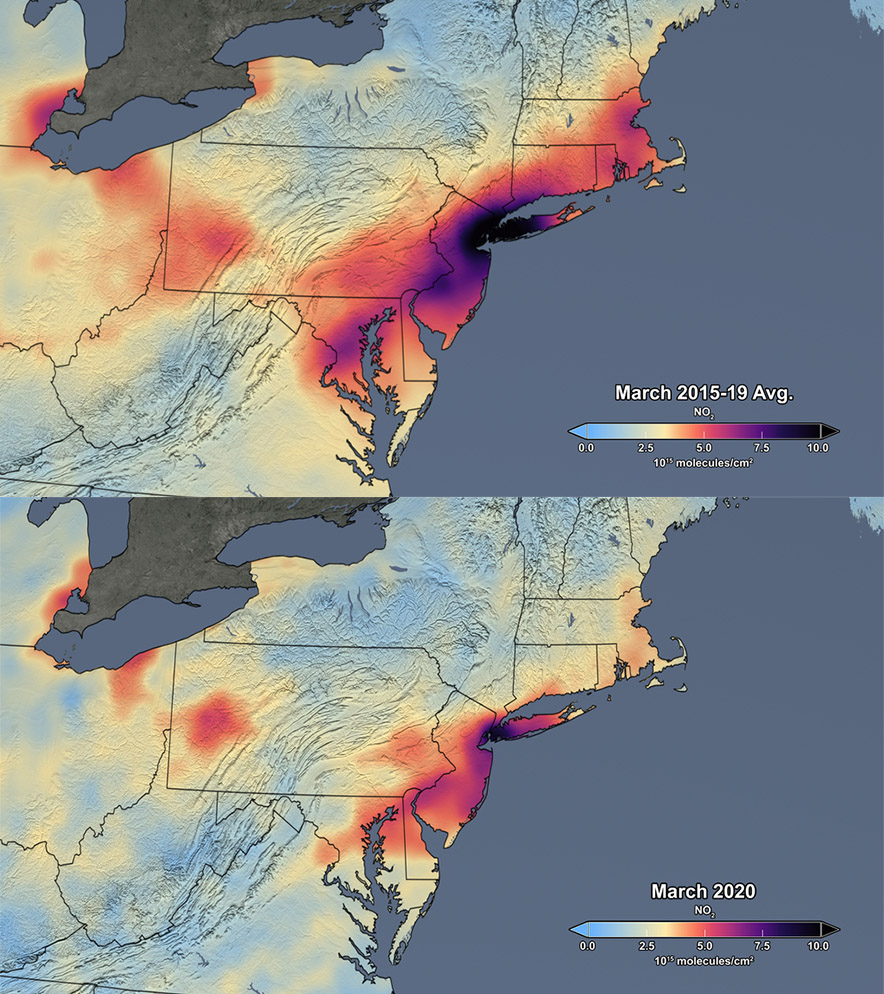

The novel coronavirus which causes the COVID-19 illness was first identified in Wuhan, China in December 2019. By January 2020, Chinese authorities had shut down local businesses and implemented transport restrictions. Satellites monitoring pollution for NASA and the European Space Agency have since detected a marked decrease in airborne NO2 after the shutdowns.

This pollutant is mostly emitted from burning fossil fuels in transport, industry and electricity generation, which makes it strongly linked to human activity. NO2 levels are also influenced by the weather and various atmospheric processes, so they must be interpreted carefully.

NASA scientists say the drop was first apparent in Wuhan, but eventually spread across China. Taking into account weather-related fluctuations and yearly pollution decreases associated with the Lunar New Year holiday, there’s strong evidence that the NO2 drop is at least partly related to the COVID-19 shutdowns. Wuhan also experienced a 44 per cent drop in concentrations of PM2.5, another ambient pollutant strongly linked to human activity with particularly detrimental health impacts.

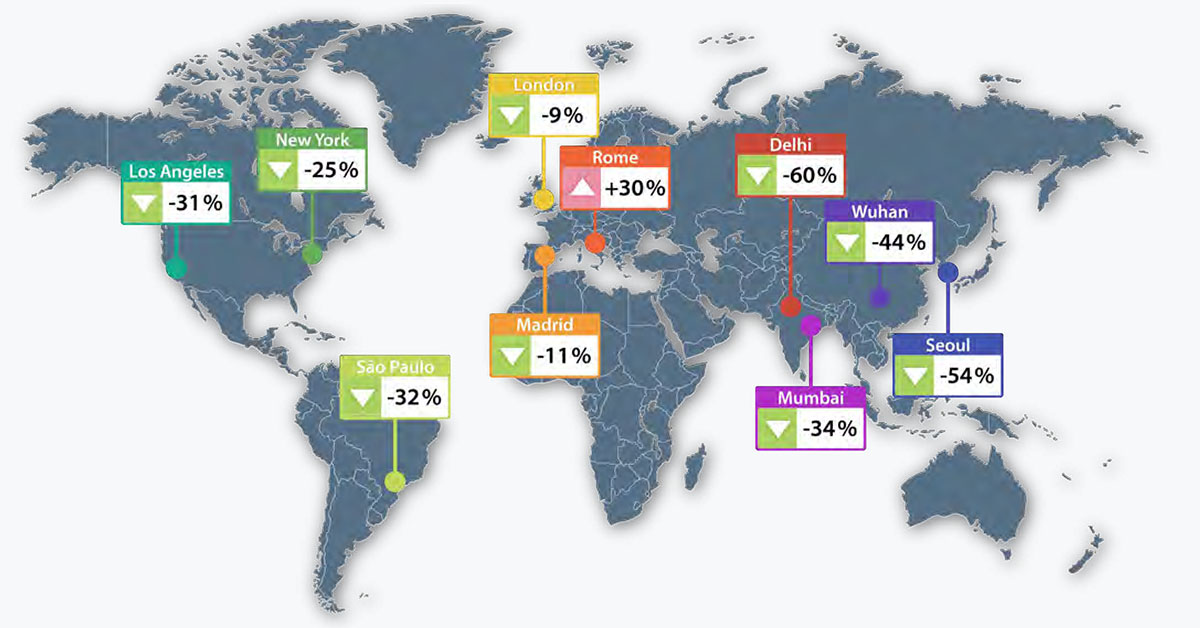

Other major cities have also observed lower air pollution levels, with measurable reductions in NO2 and PM2.5. Across March 2020, average NO2 concentrations in Rome were 26–35 per cent lower than for the same period in 2019, according to the European Environmental Agency. (On the other hand, levels of PM2.5 actually increased during Rome's shutdowns, which may be attributed to the higher use of residential heating.) Similar trends were observed in other European cities that implemented lockdown measures, such as Madrid, which experienced a 51 per cent reduction in average NO2 concentrations.

In the UK, London and Edinburgh have experienced a drop in NO2 levels by up to 60 per cent compared to the March/April period last year. US cities like New York and Los Angeles have observed huge improvements in air quality and notoriously polluted cities such as Delhi, Bangkok, São Paulo and Bogotá are also reportedly enjoying clearer skies. In a report collated by air quality information and tech company IQAir, 9 out of 10 major global cities that imposed COVID-19 shutdowns measured PM2.5 reductions of 25–60 per cent compared to the same period last year.

The reduction in air pollution has even had significant health benefits, although this does not minimise the devastating impacts of the pandemic, which as at early May 2020 had resulted in millions of cases and hundreds of thousands of deaths worldwide. According to calculations carried out by Earth science Assistant Professor Marshall Burke at Stanford University, the reduction in air pollution caused by the industrial shutdowns is likely to have saved between 53,000 to 77,000 lives in China alone. While exposure to outdoor air pollution doesn’t damage our health as rapidly as infectious diseases might, WHO estimates that it is responsible for 4.2 million premature deaths each year by increasing the risk of cardiovascular and respiratory disease, cancer and adverse birth outcomes. A preprint study from Harvard University links exposure to air pollution with greater mortality in COVID-19 cases.

However, as China focuses on recovering from the economic impacts of COVID-19, its emissions are creeping up again. Analysts at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air reported that COVID-19 shutdowns temporarily reduced China’s CO2 emissions by a quarter. Coal consumption at power plants and oil-refinery utilisation bottomed out in March 2020, but have since returned to normal, as have NO2 pollution levels.

What effect will COVID-19 have on atmospheric CO2 levels?

It’s been reported that if economic and transport shutdowns continue, it will lead to the first decrease in global emissions since the 2008 global financial crisis.

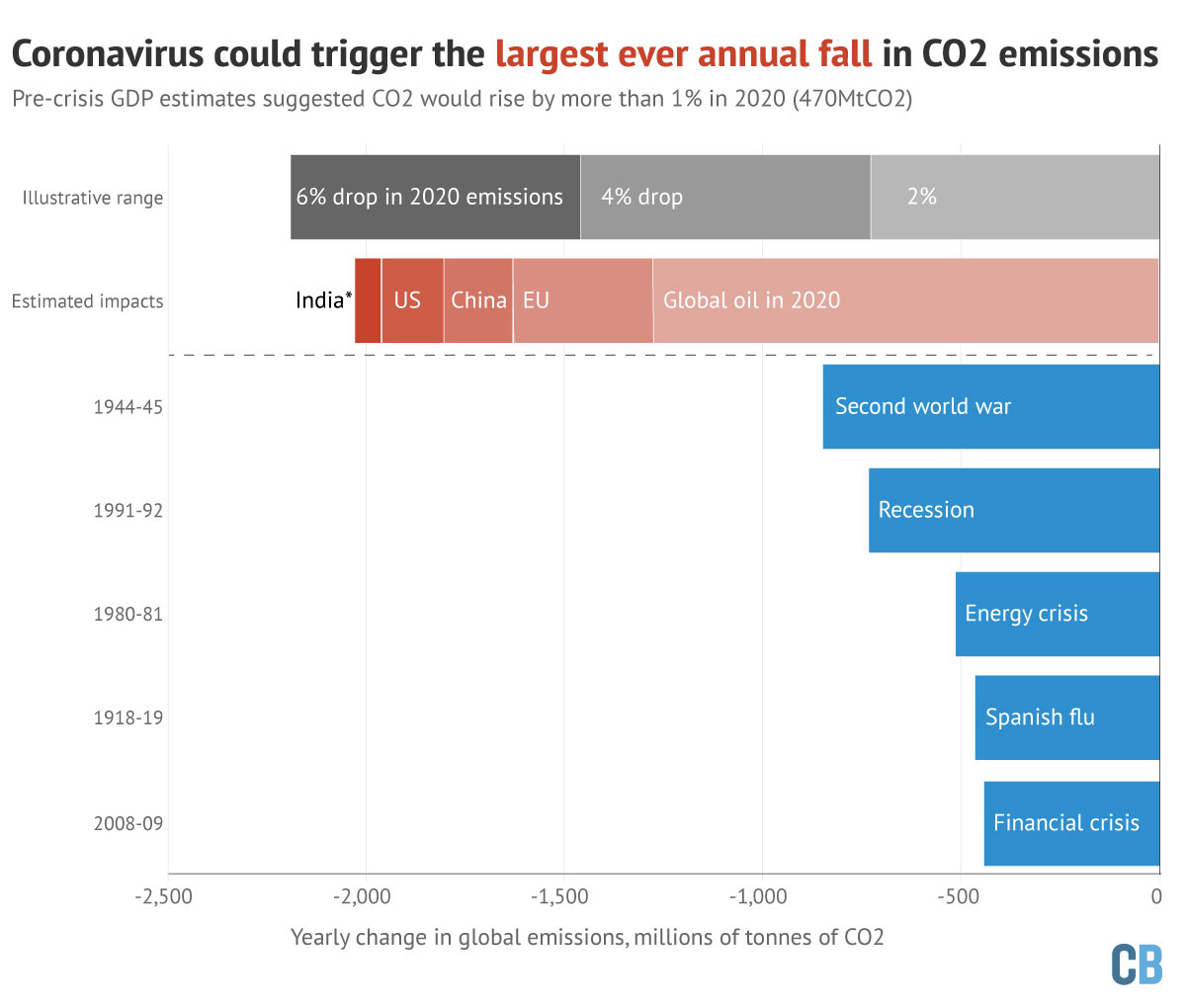

An analysis by Carbon Brief suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic could reduce CO2 emissions by 1600 million tonnes this year, which is around 5.5 per cent of total global emissions in 2019. To put that into perspective, that’s equivalent to taking 3.46 billion passenger vehicles off the roads for one year, as calculated using the Environmental Protection Agency’s Greenhouse Gas Equivalencies Calculator.

The drop would be the largest ever annual fall in CO2 emissions, greater than during any economic crisis or war since the start of the 20th century. This tentative estimate has been calculated by analysing a data set that covers roughly three-quarters of the world’s annual CO2 emissions. The authors also point out that the unprecedented nature of the crisis makes market predictions highly uncertain, particularly as we don’t know how long shutdowns will last.

So does decreasing CO2 emissions immediately lead to a drop in atmospheric levels of CO2? Unfortunately not. Atmospheric CO2 levels don’t just depend on CO2 emissions from human activity—they’re also influenced by how well (or poorly) the rest of the planet absorbs CO2. Land and ocean ecosystems removed around 30 and 25 per cent respectively of the anthropogenic CO2 created between 2000–08, leaving 45 per cent to accumulate in the atmosphere. However, ecosystem degradation and the effects of climate change diminish the ability of our ecosystems to act as carbon sinks. As a result, atmospheric CO2 levels have been rising by an average of almost 2.5 ppm (parts per million) each year since 2010.

This means that unless we continue to cap CO2 emissions to shutdown levels for an extended time, atmospheric CO2 levels won’t drop. In fact, atmospheric scientists have estimated that even with a 10 per cent drop in emissions sustained all year, we will still see atmospheric CO2 concentrations increasing by 2 ppm in 2020.

How can we make sure the environment comes out better, not worse?

Experts warn that despite lower air pollution levels in the short term, our environment may not see any long-term benefits. This situation occurred following the 2008 global financial crisis, when greenhouse gas emissions rebounded as the economy recovered. Concerns have also been raised that environmental policies will be relaxed, which is currently occurring in the US and Australia, and that investment in renewable energy technology will slow.

However, scientists, leaders and activists are pushing for an urgent public debate so that the global recovery from COVID-19 focuses on clean energy and more stringent environmental policies. In April 2020, the UN’s climate chief warned that global emissions must be capped now to meet the Paris agreement of limiting global warming to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels.

A simple way that we can implement change as individuals is one that we’re already adjusting to: travelling less. However, according to the International Energy Agency the biggest sources of global emissions are power generation, heavy transport and industry. Reducing emissions requires a transition away from fossil fuels to cleaner energies, as well as greater energy efficiency. That takes action from governments and industry leaders, not just individuals.

Ultimately, we must collectively approach our environmental crisis with the same urgency as we have the COVID-19 crisis if we are to lessen the effects of global warming.