The ins and outs of our digestive system

Expert reviewers

Essentials

- Our body contains a complex system of organs that does the job of processing our food and extracting all the nutrients we need.

- Both physical and chemical processes help to break down, digest and absorb the food as it travels through our digestive system.

- The digestive process begins in our mouth. Chewed food then travels down our oesophagus to our stomach, then to the small intestine and the large intestine. Digested food that is not needed by our bodies is passed into the toilet.

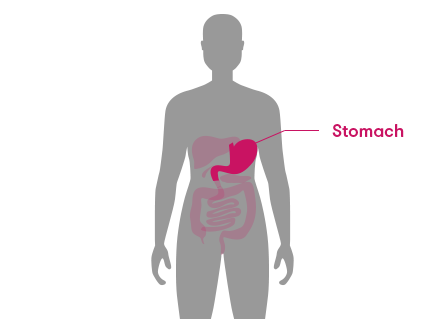

- Our stomach can comfortably hold around 1 litre of food and drink, but it can stretch to hold up to 4 litres when we eat lots! Eating more than this can cause us to throw up.

- When our stomach is full, it presses against other organs, which can make us feel uncomfortable.

Eating. Most of us are lucky enough to do it every day, and often to excess. But what happens to those three square meals and all those tasty snacks? Well, we have a bunch of organs that are collectively known as our digestive system, or gastrointestinal tract, whose job it is to process our food and get all the nutrients and goodies we need from it.

Basically, food goes in, food gets mushed around and mixed up with a heap of chemicals made by different parts of our body, some food gets absorbed, and the rest of the food comes out as waste (or a valuable resource, depending how you look at it). But what is it that makes us feel sick when we eat too much Christmas dinner?

That sickening Christmas dinner feeling

Generally, our bodies are geared to match the amount of food we eat with the energy we expend going about our daily business—a balance known as energy homeostasis. Our brain and digestive system work together to make this happen.

As our digestive system processes our food, it produces hormones, one of which is called cholecystokinin (CCK). Cells in our small intestine produce CCK when our system registers that fats or proteins have arrived in our stomach. CCK helps us to feel full as it slows down the movement of food from the stomach on to the next step of the digestive process.

An interesting thing about CCK is that foods with a high sugar content do not trigger the production of CCK in the way foods containing fats do—so sugary foods don’t make us feel as full, despite their high energy content. And here’s a tip: drinking a glass of water before eating can help to fill our stomachs and so stimulate CCK production, which helps us feel full more quickly.

It’s thought that CCK, along with two other hormones also produced in our gastrointestinal tract, called peptide tyrosine tyrosine, and leptin, also have a job to do in our brain. When the hormones combine with receptors in our brain, a neural response is triggered. It makes an announcement to our bodies that we’re full and have had enough: stop eating! This satiety response can take a bit of time to register—sometimes we eat too much because we’re enjoying our food and the announcement that we’re actually full comes a little too late.

At Christmas, or other special occasions involving food, we often ignore the announcement on purpose. This is mainly because we’re lucky enough to be presented with so much delicious food, and it would be rude to refuse your aunt’s amazing potato salad, right? So what happens when we eat too much? Why do we feel ill?

There’s a finite amount of space in our stomach—around 1 litre, although it can hold up to 4 litres before a gag reflex kicks in, causing us to throw up.

Every mouthful of food, or sip of drink we take is accompanied by a small amount of air as it travels down into our stomachs, especially if we’re drinking something fizzy, and this also helps to fill up our stomachs. Our bodies get rid of excess gas by sending it back up again—as a burp!—which can help to relieve the uncomfortable feeling.

The main feeling of discomfort comes from our full stomachs pushing out against other organs, including our diaphragm and lungs, which can make it harder to breathe. More blood flows to our digestive system as it works extra hard to process all the food, sometimes leaving our extremities feeling chilly. We might also feel drowsy, again a result of our digestive system working so hard. Our blood sugar peaks, then drops.

Another problem can come from the extra stomach acid that’s produced to process all the food we’re eating. This acid can irritate the stomach and creep up into the oesophagus, causing heartburn. Some people take antacid tablets to help with this. They contain an alkaline, or basic, substance to neutralise the acid. The chemical reaction that neutralises the acidity produces more gas—which means more burps!

Why do we do it?

We know we’re going to feel sick, and probably guilty, after that third helping of dessert. But we do it anyway, because food is so tasty. Our brains release dopamine when we eat something we enjoy. This is a chemical that governs our brain’s reward and pleasure centres; it makes us happy.

Our brains can be fickle, too. Often the reward from a particular taste can get old, and that food stops triggering the same level of pleasure in the brain. We feel the need for a new sensation—an impulse that’s usually pretty easily fulfilled at Christmas dinner. We may move from the seafood entrée to the baked ham, then on to the potato salad, then to the chicken, and finally—a whole new ball game—the dessert. End result: our stomachs are really full.

In some cases, it’s the kind of food we’re eating that makes us want more. Some food types stimulate a stronger salivary response. As we eat, our salivary glands produce saliva, which helps to spread the flavour of the food throughout our mouth and over our tastebuds. Certain foods, emulsified ones like butter, chocolate and mayonnaise, as well as sauces and glazes, encourage this response, which makes our brain happy—and makes us want to eat more of it.

Another factor which can contribute to the Christmas dinner feeling is the social aspect of the event. Studies have shown that people eating in groups are often influenced by the eating behaviours of their companions. Apparently, when eating with someone expressive and exuberant, we’re more likely to match that person’s food intake—be it small or large.

So what to do if that uncomfortable, ugh-I-need-to-undo-my-jeans feeling kicks in? Well, don’t go for that little lie-down on the couch you’re contemplating—this will actually hamper the digestive process. A brisk walk around the block, or a few trips to and from the kitchen to clear away the dishes, is a much better idea. And just a heads-up: remember that nice chemical dopamine, the one that makes our brain happy? It’s also released by exercise, making that walk around the block a doubly good option!

What actually happens to our food?

So, what’s actually happening to all that dinner as you lie on the couch (but only after you’ve gone for that brisk walk around the block)? How does our digestive system work?

Food goes in

First of all, our brain makes a decision to put some food in our mouths—either we feel hungry or simply decide that something is delicious and we want to eat it.

Hunger is usually triggered when our blood sugar levels are low, which can happen after a period without food. Cells within our stomach and pancreas produce a hormone called ghrelin, a peptide hormone that acts on our brains (the lateral hypothalamus region) to make us feel hungry. Ghrelin levels increase before we eat, then decrease after we’ve had some food.

Even just the sight or smell (ooh, is that bacon?) of food can trigger a response in our brain that prompts the creation of some of the enzymes required for digestion. The salivary glands start to produce saliva, making our mouths water. Our stomachs may start their muscular contractions, giving us hunger pangs.

So, the beginning of the process: food enters our mouth. Hello, chocolate.

Food gets mushed around

Once in, the food is firstly broken up by our teeth and jaws, and our salivary glands produce saliva, which our tongue helps to mix with the food. The saliva contains enzymes, which start to break things down chemically. For example, the enzyme ptyalin converts starches into simple sugars.

The chocolate, broccoli, or whatever it is we’re eating is mushed into a mouthful of wet, chewed-up food, called a bolus.

Next, our tongue pushes the bolus to the back of the mouth (the pharynx), and we swallow it. It’s now on its (hopefully) one-way trip through the oesophagus to the stomach. It’s pushed through the oesophagus by waves of muscular contractions called peristalsis. These contractions are so strong that our food will get to our stomachs even if we’re hanging upside down.

At the bottom of the oesophagus is the lower oesophageal sphincter, a muscular ring which opens to allow the bolus into the stomach, then closes to stop any stomach contents coming back up the oesophagus again. Reflux is the result of this muscle not working properly.

Now the bolus is in our stomach, where very strong acid (hydrochloric acid, HCl) kills bacteria and germs, and helps to break down the food. Various chemicals called enzymes continue their work of digestion: breaking down proteins into amino acids, fats into fatty acids and complex carbohydrates into simple sugars. An essential protein called intrinsic factor is also found in the stomach. It helps us absorb vitamin B12.

The strong muscular wall of our stomach physically processes our food, contracting at a rate of three times a minute, grinding and churning the food and combining it with the enzymes into a goopy, soupy mixture called chyme (from chymos, Greek for juice!). Our stomach then pushes the chyme into the beginning of our small intestine, or duodenum.

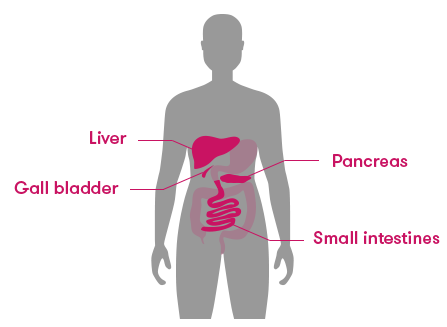

Alkaline enzymes called amylases are sent from our pancreas to process carbohydrates into simple sugars, and then cells lining our duodenum produce more enzymes to finish off the job. Other pancreatic enzymes continue to break down proteins into amino acids. Our pancreas is connected to our duodenum by a tube, and the enzymes are sent to the duodenum when the food arrives.

When our duodenum registers that fats or proteins have arrived, it produces CCK, the hormone mentioned earlier that plays a role in sending satiety signals to our brain. As well as slowing the progress of food from our stomach to our duodenum, CCK stimulates the release of bile, which is made by our liver and stored in our gall bladder until it’s needed. Bile is sent to our duodenum through a tube called the bile duct.

Bile enters the duodenum to help neutralise the strong stomach acids and act as an emulsifier, helping fat to mix with water. It also enables the digestion of vitamins A, D, E and K.

After spending some time in the duodenum mixing with all the enzymes and bile, the chyme goes on through the rest of the small intestine. In adults, the small intestine is between 3.3 and 6.6 metres long, depending on the size of the person. More waves of contractions (again occurring around three times per minute, but here called segmenting contractions) push the chyme through our small intestine on a journey during which most digestion and nutrient absorption takes place.

Food gets absorbed

After all the fats, proteins and carbs from our food have been broken down and digested, they’re absorbed. This mostly happens in our small intestine. As the food is being squeezed along its trip through our intestine, specialised cells in the wall lining strip out all the sugars, amino acids, fatty acids, vitamins and minerals. These are absorbed and sent off through our bloodstream to our liver. Our liver processes all the proteins, sugar and fats it receives into energy to feed our body’s cells.

When we consume more food, and thus energy, than our bodies need, the excess is stored as fat in adipocytes, also known as fat cells.

Food comes out

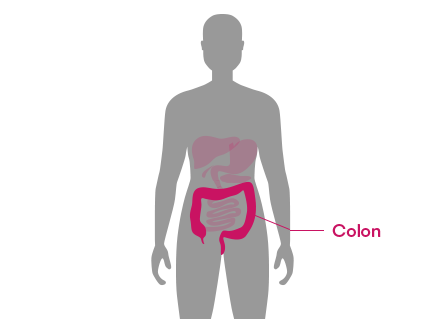

Peristaltic waves push the rest of our indigestible food into our large intestine, or colon. Our colon doesn’t really do any more digestion work, although bacteria that reside here do continue to digest any remaining amino acids that may still be hanging around. They produce not-particularly-pleasant-smelling nitrogen gas, responsible for the phenomenon known as passing wind.

Our large intestine’s main job is to complete the process of absorbing water and electrolytes—magnesium (Mg), potassium (K), calcium (Ca) and sodium (Na). The rest of the dry(er) unabsorbed material meets up with some bile containing waste products our liver didn’t want, which gives the final end product of our digestive system its characteristic brown colour. More muscular contractions, this time in our rectum (and more actively controlled by our brain) and the final product, faeces—or poo—is excreted out from our bodies. Job done.

Good work, gastrointestinal tract!