Five anecdotes from renowned Aussie scientists that you probably didn’t know

Nestled in a cosy corner of Canberra’s Shine Dome, the Australian Academy of Science’s archives hold a sprawling collection of stories from some of the country’s most renowned scientists. While the collections shine a light on their scientific processes and research, they also bring history to life: baring personal triumphs, struggles, and unexpected anecdotes.

Here are five anecdotes about well-known scientists drawn from their carefully curated collections.

Professor Frank Stillwell nearly died of carbon monoxide poisoning

“Upset today,” writes Frank Stillwell OBE FAA, beginning his account of a near-fatal carbon monoxide poisoning in December 1912.

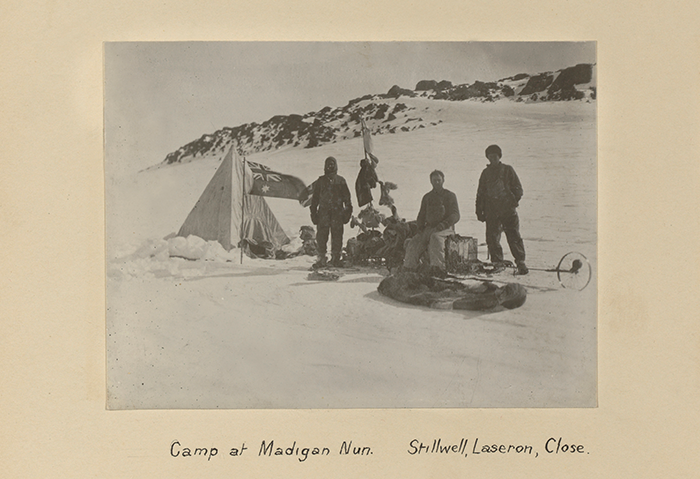

An Australian geologist, Stillwell was in Antarctica, leading one of six sledging parties that had left the base camp of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition to explore the continent. Stillwell and his colleagues John Henry Close and Charles Laseron conducted two field trips along the coast of Commonwealth Bay.

Sheltering in their tent, the party of three had lit a stove (for warmth and cooking). But Close realised that the stove was filling the enclosed space with poisonous carbon monoxide. While his colleagues laid unconscious, Close punched an air hole in the fabric of their tent with an ice axe—quick thinking that saved the party's lives.

Frank Stillwell OBE FAA and colleagues John Henry Close and Charles Laseron who surveyed the coastline east of Commonwealth Bay as part of the Australasian Antarctic Expedition during the summer of 1912-13.

Read more about Professor Frank Stillwell

Sir Douglas Mawson was almost stranded in the Antarctic

“Still no Mawson,” Professor Frank Stillwell writes in January 1913.

While Stillwell, Close and Laseron explored Commonwealth Bay, expedition leader Sir Douglas Mawson OBE FAA FRS led the Far Eastern Shore party to survey the glaciers east of Cape Denison. He was accompanied by Xavier Mertz and Lieutenant Belgrave Ninnis.

Five weeks after setting out, tragedy struck, when Ninnis and six sled dogs fell into a crevasse—along with much of the party’s supplies. Mawson and Mertz immediately turned back but were forced to eat their remaining sled dogs to survive and suffered vitamin A poisoning. Mertz perished just four days after Stillwell wrote of his worry for the party.

Mawson, in a severely weakened state, made it back to base camp just in time to see the Australasian Antarctic Expedition’s ship Aurora, leaving for Australia. A shore party had been left to wait for him, but it was too late for the ship to turn, and Mawson found himself forced to spend a second winter in Antarctica.

Read more about Sir Douglas Mawson in his memoir

Professor Frank Fenner lost his luggage en route to the Nobel Prize lectures

“No luggage yet... we go [to the Nobel Prize lectures] at 1.45 pm so if it doesn’t come before 1 pm I will have to go in what I stand up in!” - Frank Fenner

Frank Fenner AC MBE FAA FRS, best known for his extensive contribution to the understanding of viruses and work with the Smallpox Eradication Program, writes of travelling to Stockholm in December 1996 to celebrate Professor Peter Doherty AC FAA FAHMS FRS and Professor Rolf Zinkernagel FAA, who were being awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine. “Slept in!” Fenner wrote. “Almost missed plane, lost luggage which arrived just in time for the award ceremony [tails and white tie], but not in time for the lectures.” Fortunately, the black pants and blue jacket combination he was wearing while travelling suited the ‘dark suit’ dress code for the lectures, and he was able to blend in seamlessly with the crowd.

Fenner is widely known for his significant role to international public health as Chair of the World Health Organization (WHO) Global Commission for the Certification of Smallpox Eradication. His travel diaries cover five decades of professional life and touch on an extensive contribution to the understanding of viruses and the literature of microbiology. They are also an unexpectedly rich personal archive recording Fenner’s thoughts on the implications of his work, broad-ranging intellectual interests, international collaboration and environmental advocacy.

Frank Fenner before the World Health Assembly in Geneva, 1980 declaring smallpox successfully eradicated.

Read more about Professor Frank Fenner and his diaries.

Sir Ian Wark witnessed the lead-up to Mussolini’s March on Rome that resulted in the takeover of Italy

“Milan is a big place; it has 800,000 inhabitants—but most are on strike.”

Sir Ian Wark CBE FAA observed the leadup to Mussolini’s March on Rome while visiting Milan in 1922. Later, he made a note in the margins of his diary: “the loyalists (fascists) completely took over Italy in November the same year.”

Wark was undertaking an 1851 Exhibition Scholarship at University College London at the time, conducting research in the infant field of mass spectrometry. He took the opportunity seriously: travelling with fellow students, assuming an active role in college leadership, attending meetings of learned societies and spending weeks in the lab with Nobel Laureate Sir William Henry Bragg OM KBE FRS. He returned to Australia in 1924 and became one of the country’s most influential chemists.

Read more about Sir Ian Wark in his memoir

Sydney’s Rodd Island was declared a quarantine facility… to house a French movie star’s pet terriers

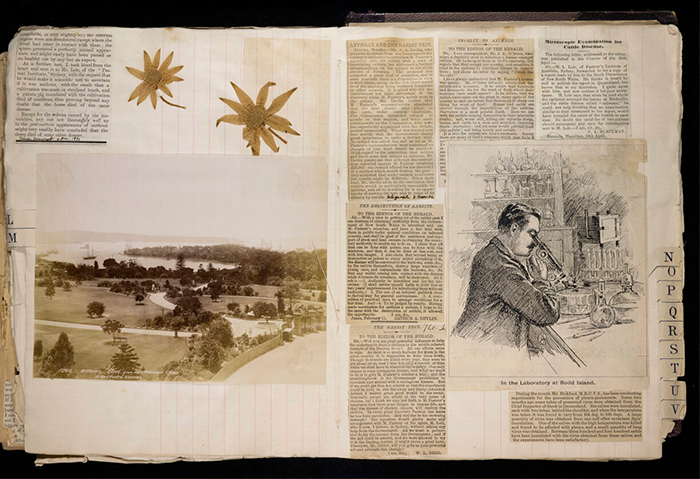

Adrien Loir, the nephew and protégé of renowned French scientist Louis Pasteur, established a Pasteur Institute on tiny Rodd Island in Sydney Harbour in the late 1880s—initially in a bid to claim the £25,000 reward (A$10 million in today’s terms) offered by the NSW Government for control of the rabbit plague in the state, and then as a place to study and manufacture livestock disease vaccines (to prevent, for example, anthrax, bovine pleuropneumonia and blackleg of cattle). The profits from this venture helped fund the Pasteur Institute in Paris.

While in Australia Loir kept two massive scrapbooks containing pressed flowers and steamship tickets alongside obscure media coverage, cartoons, letters and journal articles in French and English.

When French actress Sarah Bernhardt arrived in Australia in May 1891, she neglected to go through the quarantine process for her two pet terriers, Star and Chouette, and the NSW Government confiscated both dogs. Bernhardt, the superstar of her age, was threatening to leave the country.

Loir convinced the government of Premier Sir Henry Parkes to declare Rodd Island a quarantine facility and let him care for the dogs while Bernhardt continued her Australian tour.

Finally, while this didn’t make the top five, this snippet from a letter to Sir Mark Oliphant AC KBE FRS FAA FTSE from Sir Robert Menzies FAA FRS in 1957 regarding the Shine Dome is worthy of an honourable mention:

‘“Dear Sir Mark—thank you for your letter and the plan for the headquarters of the Academy of Science. I am very depressed about Canberra architecture. Whether your building will elevate my spirits I do not know, but I doubt it. Anyhow, good luck.”.

While the archives are replete with such fascinating tales, there are many more untold stories in danger of a dying a quiet death. You can help us preserve this history by supporting the Academy’s digitisation project.

Architectural render of the Academy of Science by Roy Grounds (1958)

For more stories from the Academy’s digitised archives, visit the Academy website.

This article was written by: Wendy Wakwella, Communications Manager, and has been reviewed by the following experts: Clare McLellan, Archivist, Australian Academy of Science.