Why are some blood types incompatible with others?

Ever wondered why some blood types aren’t ‘compatible’ with others? Or what would happen if you got the wrong blood type during a transfusion? It all comes down to antibodies.

Antibodies are specialised proteins that are produced in response to anything that your immune system might need to fight off, such as bacteria and viruses. Consider them the first ‘identification’ step of the immune system, trying to find anything that doesn’t belong.

Despite the similar name, antibodies are not to be confused with antigens. An antigen is any kind of molecule, such as a protein or a carbohydrate, that can be recognised by the immune system—the antibodies target whichever antigens it identifies as being foreign invaders.

It is important though for the antibodies to not identify antigens that do belong. They’re also produced based on the antigens that are not already present on your red blood cells. For example:

- A type blood has anti-B antibody in the plasma

- B type blood has anti-A antibody in the plasma

- AB has neither A nor B antibody in the plasma

- O has both A and B antibody in the plasma.

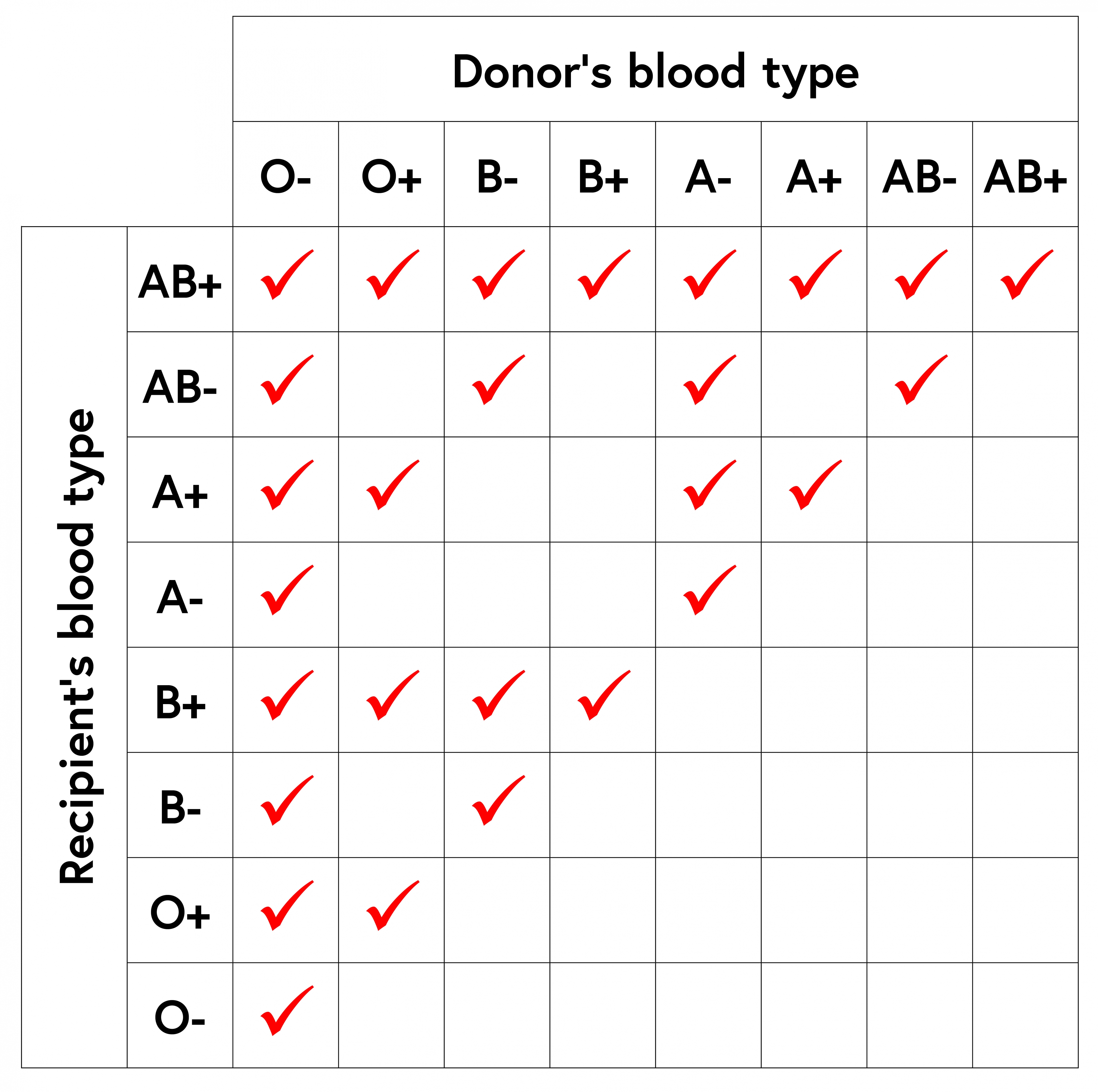

This means that it’s important to get the right donor blood type if you need a transfusion. If an antigen is introduced into your body that isn’t there normally, your system will identify it as an intruder. The immune system will go into attack mode and antibodies will be produced to help fight off the unfamiliar visitors.

For example, if someone with Type O blood (blood with no A or B antigens on the surface of red blood cells) received red blood cells donated from someone with Type B blood (blood containing B antigens), the recipient’s immune system would immediately identify the new blood cells as foreign and seek to destroy them.

Antibodies attack by binding to the foreign antigens on the surface of red blood cells. This ultimately causes those red blood cells to rupture, destroying them entirely. In small amounts, rejected blood can be filtered out by the kidneys, but larger transfusion amounts could cause kidney failure and, potentially, death.

However, if the situation were reversed, and Type O red blood cells were donated to someone with Type B blood, no unfamiliar antigens would be introduced into the recipient’s body, so the blood cells would not be identified as ‘intruders’ by the immune system. This is why Type O red blood cells (more specifically, O negative blood) can be donated to anyone, regardless of blood type, and is known as a ‘universal donor’.

What about plasma donations?

Although people often donate whole blood, platelets and plasma from donors are also used. Donations are separated into different components before transfusions occur, depending on the needs of the recipient.

Your blood type is important not only when it comes to donations of red cells, but also when we’re talking about donations of plasma, which contains certain antibodies depending on your blood type. So, if someone with Type O blood was to try and donate plasma to someone with Type B blood, that plasma would contain anti-A and anti-B antibodies. Those anti-B antibodies would then attack the red blood cells of the Type B recipient.

Blood type and pregnancy

Blood type compatibility is clearly very important when donating and transfusing blood products, but blood type incompatibility can also become an issue during pregnancy, if a mother’s blood type is Rh negative, but her unborn child’s is Rh positive.

These differences in blood type can become a problem if the baby’s blood enters the mother’s bloodstream—for instance, during childbirth. In a mother with Rh negative blood, the baby’s D antigens can be identified as foreign, with the mother’s body producing antibodies against them.

This usually only becomes a problem when the mother is first exposed to her baby’s Rh-positive blood and tends to become more of an issue for any pregnancies after the first. If antibodies produced by the mother attack the unborn baby’s red blood cells, the unborn baby’s destroyed or damaged red blood cells may not be able to carry oxygen around their body. This could result in miscarriage or stillbirth. If the baby is born alive, they may have jaundice and anaemia.

To help prevent this, Rh negative mothers in Australia receive an injection of Anti-D immunoglobulin during pregnancy (including their first pregnancy), or shortly after birth, which helps stop their immune system from making anti-D antibodies.