History of the Shine Dome

The story of its construction

Completed in 1959 and reflecting some of the more adventurous architectural ideas of that time, the Shine Dome (previously known as Becker House) remains one of the most unusual buildings in Australia.

The dome—roof, walls and structure combined—dives down beneath the still water of its moat to give the sense that it is floating. From the walkway between the moat and the inner walls, the arches provide a 360° panoramic sequence of 16 views of the capital city and the hills beyond.

The Shine Dome was conceived before Canberra's Lake Burley Griffin existed, before microchips, and before manned space travel. It was created in the visionary scientific era of Sputnik, the first artificial satellite to orbit the Earth.

The dome came about because the Australian Academy of Science needed a home. In the early 1950s, under the founding Presidency of Sir Mark Oliphant, the new Academy and its 64 Fellows set about finding funds to create a building of its own. The Academy, which had been using offices in the Australian National University, recruited some eminent industrialists to its cause and received its first cheque (for £25,000) from BHP. Thus encouraged, Fellows both provided funds and encouraged their business associates to do the same. The dome, which cost a total of £260,000 to build, was completed in 1959 and named Becker House, recognising Sir Jack Ellerton Becker's £100,000 donation.

Once the Academy had found a suitable site, the next step was to select an architect. Six architects were invited to submit plans to a competitive process, and on 1 December 1956 the Academy's Building Design Committee met in Adelaide to look at them. The committee wanted a building that would be of a very high order aesthetically, judged from a non-traditional standpoint.

The committee settled upon the most radical design and their decision was unanimously approved by Council. Grounds, Romberg and Boyd were seen as the most influential Australian architects of their time.Roy Grounds was the sole architect on the Academy's building: it was his design that won the commission.

Unique features and challenges

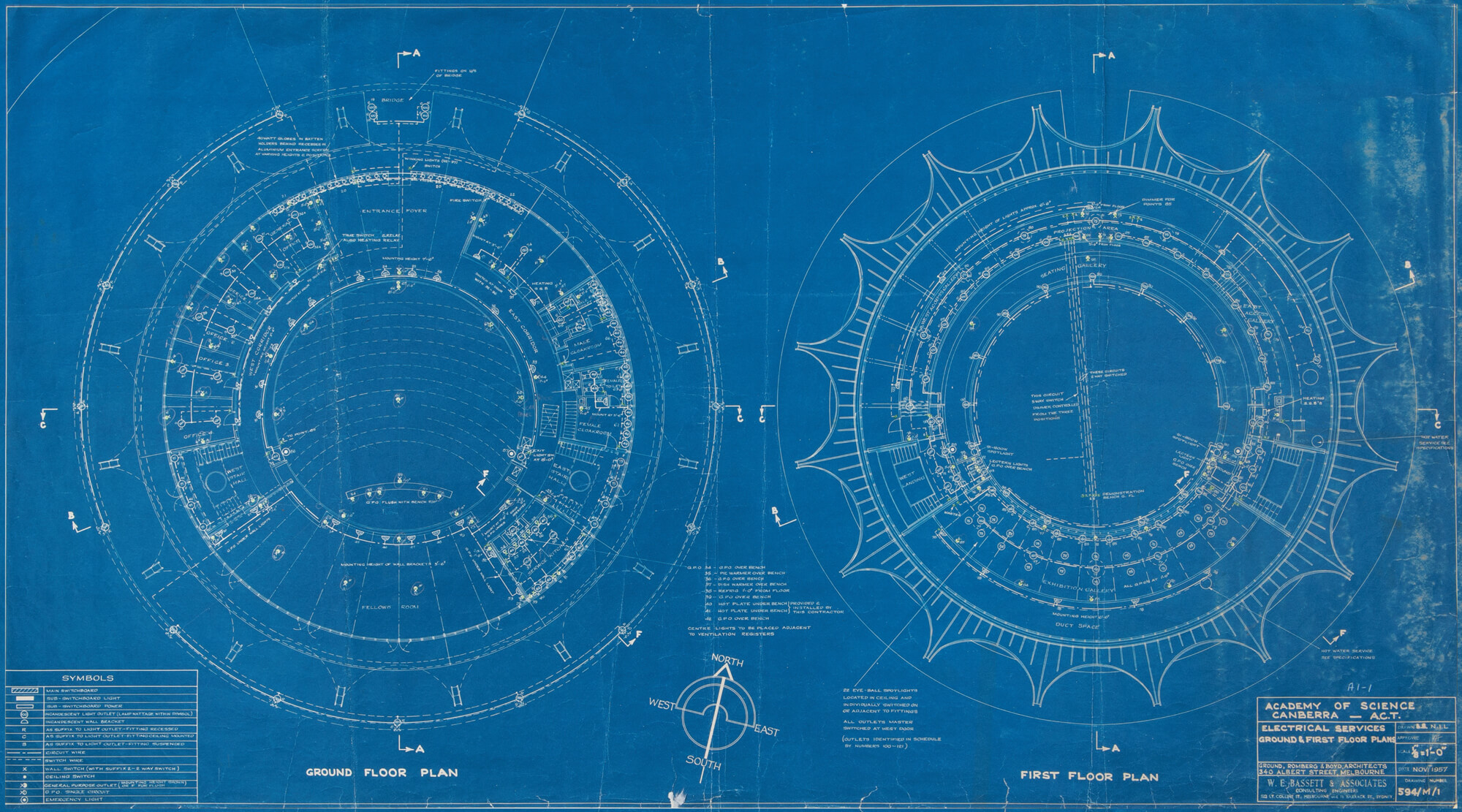

The radically different building created radically different problems for the architects and engineers involved. Some doubted it could be built. Nobody knew how to calculate the stresses created by a 710 tonne concrete dome perched on 16 slender supports. This was vital, because if they got it wrong the whole dome might collapse when the building supports were taken away. In the end they grappled with the problem by building a one-fortieth scale model to see if it would work.

Those who trusted the model were proved right. When the massive concrete dome was built and the forest of wooden formwork and supports removed, the top of the dome dropped less than a centimetre as it took its own weight. It was a triumph for those who worked on the calculations and the model.

But getting the 'roof' on was only half the battle. In the centre of the dome was a lecture theatre for 150 people – and the big concrete umbrella did some strange things to sound. Again, the problems were new ones, and it took a great deal of work by acoustic engineers to get the sound right. The solution was to use a complex series of acoustic baffles to control the sound. Some were suspended from the ceiling and others built as part of long wooden panels on the walls. After much trial and error, the sound problem was solved.

Then a whole new and totally unexpected problem emerged. It became apparent that the elegant eucalyptus sound baffles gracing the walls created a form of optical interference, rendering about half of the people in the room nauseous. It took quite some time to find a solution, but eventually a Fellow, Dr Victor Macfarlane, who worked at the John Curtin School of Medicine at the ANU, came up with the idea of filling in the visually offending gaps with strings. This fixed the optical problem without spoiling the acoustics.

The concrete roof of the dome is sheathed in copper – and under the copper is a layer of vermiculite which partly insulates the interior from outside temperatures. This provides a degree of thermal inertia and the temperature of the dome's underside is roughly an average of the outdoor temperature of the previous 24 hours. It can become unpleasantly hot after a February heatwave or chilly after an August cold spell. However, a natural gas heating system helps keep the building warm in winter. In the summer the sloping roof shields the windows from direct sunlight.

Opening the dome

The dome's foundation stone was laid on 2 May 1958 by Prime Minister Robert Menzies, and founding Fellows Sir John Eccles, Sir Mark Oliphant. Each spoke eloquently about the founding of the Academy and the importance of science to Australia and the world. On 6 May 1959 luminaries of science and politics gathered to witness the Governor-General, Sir William Slim, officially open the dome.

Later additions

In 2000 the dome was completely restored and updated with a new cooling system. These major works were supported by a donation of $1 million from a Fellow, Professor John Shine, and a grant of $525,000 from the National Council for the Centenary of Federation. In recognition of this donation, the building is now named the Shine Dome.

A capital landmark

For its unique architecture and status as a landmark, the Shine Dome was included in the National Heritage List on 21 September 2005. For many years the Dome has been an iconic landmark of the national capital. It has featured in news backdrops, on posters, postcards, teatowels and even as a souvenir fridge magnet. The Shine Dome, which has won a number of national and international architecture awards and citations, continues to fascinate visitors to Canberra.