Contents

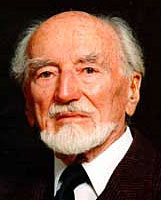

View Dr Phillip Law (1912-2010) photo gallery

You can order the DVD from the Academy for $15 (including GST and postage)

Dr Phillip Law was interviewed in 1999 for the Australian Academy of Science's '100 Years of Australian Science' project funded by the National Council for the Centenary of Federation. This project is part of the Interviews with Australian scientists program. By viewing the interviews in this series, or reading the transcripts and extracts, your students can begin to appreciate Australia's contribution to the growth of scientific knowledge.

The following summary of Law's career sets the context for the extract chosen for these teachers notes. The extract shows that many different areas of science and technology contributed to his successful Antarctic expeditions. Specialised equipment (eg, clothing and vehicles) had to be designed and scientific support for expeditions came from such departments as the Bureau of Meteorology and the National Mapping Office. Use the focus questions that accompany the extract to promote discussion among your students.

Phillip Law was born in Tallangatta, Victoria in 1912. His family moved to Hamilton, Victoria where he attended Hamilton High School. Law was educated at Ballarat Teachers' College and worked as a secondary school teacher in Hamilton and Geelong before beginning study at the University of Melbourne. He received his MSc in physics in 1941.

During World War II, Law continued his research at the University of Melbourne with various wartime projects and was secretary of the Optical Munitions Panel (later the Scientific Instruments and Optical Panel).

In 1947-48 Law was involved in the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) trip to Macquarie Island and Antarctica. He was appointed leader of ANARE and director of the Antarctic Division of the Department of External Affairs in 1949. He personally led 23 voyages to Antarctica and the sub-Antarctic regions, and directed ANARE activities that resulted in the mapping of 4000 miles of coastline and 800,000 square miles of territory. In 1954 he founded the Mawson, Davis and Casey bases in Antarctica.

Law resigned from the Department of External Affairs in 1966 to become the executive vice-president of the Victoria Institute of Colleges. He held this position until 1977 during which time the technical colleges were transformed into institutes of technology offering diplomas, degrees, and higher degrees based on post-graduate work.

Law has written several books – ANARE: Australia's Antarctic Outposts and three autobiographies. He was awarded an honorary DAppSc by the University of Melbourne in 1962.

Law was honoured as a Commander (Civil) of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in 1960. He was awarded the Officer of the Order of Australia (AO) in 1975, and Companion of the Order of Australia (AC) in 1995. He was elected a foundation Fellow of the Australian Academy of Technological Sciences and Engineering in 1975, and a Fellow of the Australian Academy of Science in 1978.

From nothing onwards – development by design

Interviewer: Phillip, from my reading, one of the highlights of your ANARE period would have to be the efficient logistical background to those very complex operations. Would you like to comment on that?

Yes. This was a case of developing from nothing onwards. We had to design all sorts of different aspects of what we were into. The logistics behind an Antarctic Division is an immense array of different disciplines – the choice of radio sets, tractors, the design of food for sledging purposes and also for station purposes, the design of clothing. We were the first to design modern clothing for Antarctic work, because we were down there before the IGY started, before the big nations came in. I thought that in the IGY our clothing was superior to that of the Americans and others because it was all done by collaborative discussion between the boys and myself, tossing ideas round, selecting the best things. Our design of Antarctic clothing proved over years to be the best.

The question of vehicles was very difficult. In the early days, we started dog-sledging and man-hauling, but then you had to get vehicle-hauled devices. The only vehicle available for over-snow travel of that sort was a Weasel – a Studebaker vehicle with tracks, designed by the Americans for the Norwegian campaigns of the war. The campaigns didn’t ever come off, the vehicles were left in France, and a French expeditioner, Paul-Emile Victor, began using them in Greenland and then in Antarctica. From him we learnt that these were available, but we found that, although they were fine as scout cars, they were no good for pulling: their transmissions would break down. They were never designed as towing vehicles.

If we were going to tow things, we thought, we had better get something which was designed for towing. So we switched from Weasels to tractors. We homed in on Caterpillar tractors and started with D4 Caterpillars. This revolutionised the travel, because you could have a Caterpillar tractor with a tractor train of things behind it – a sledge full of fuel, sleds full of scientific equipment, a little scientific cabin for housing the drilling mechanism for ice-core work, a live-in caravan so you didn’t have to put tents up. Tractor trains became used then all over Antarctica for international work.

The biggest tractor train effort in my day was run by the men at Wilkes, under Bob Thompson. He went on a tractor journey to Vostok, a deserted Russian station in the heart of Antarctica, at a height of about 13,000 feet and very cold. That was 900 miles from Wilkes to Vostok and 900 miles back – 1800 miles with the tractor going at about three miles an hour. The Caterpillars on that trip ran at temperatures lower than any tractor in the world had ever operated. This was great stuff.

We were the first people in Antarctica to design huts which gave individuals private cubicles. Before that, everything was on a bunkhouse design. We were the first to build an aircraft hangar in Antarctica. It’s still there. And so on.

We even designed a publications system. All the scientific information coming from our stations had to be disseminated round the world in scientific publications. Some were the traditional publications in subject areas, but we decided that we needed a lot of other publications of a more general nature. So we set up a system of ANARE Reports, which were divided into sections. We appointed a publications officer to look after all this, and I was the editor of the scientific publications of the Reports for several years until my chief scientist, Fred Jacka, took it over. Over the years, a great spread of ANARE Reports has surfaced as a result of that publications system.

The intricate detail and design in a variety of areas were a key to success in Antarctic work – quite apart from the design of Antarctic programs and all the Antarctic equipment necessary for those, which is another matter again.

Vital support

What sort of scientific support in Australia did you have for your programs?

Various government departments were fundamentally important to the success of this work. The most obvious one was the Bureau of Meteorology. Our weather comes up from Antarctica, so meteorology is the most obvious scientific work to be attacked there. Antarctic meteorology is fundamental to studying the weather patterns in the southern part of Australia.

The National Mapping Office provided the surveyors and directed the mapping of the results of their explorations. All the Antarctic maps and the place names work that we did on them finished up with that office for map production.

The Bureau of Mineral Resources was a most important government department, handling the geophysics and the geology – particularly in the early days, when we had hopes of getting minerals of value from the Antarctic. They handled the major geophysical work from the IGY also – geomagnetism and seismology.

Then there was the Ionospheric Prediction Service, a small unit which set up ionospheric measuring devices in stations to help to predict the sort of frequencies you needed for the best radio transmission possibilities, which are concerned with reflections from our ionosphere.

I should also mention CSIRO and the universities. As time went on, the universities became more and more involved. In the early days they didn’t know enough about Antarctica and missed the opportunity to get into it, but now they are scrambling over each other for a place in the Antarctic work because it is proving so profitable.

Select activities that are most appropriate for your lesson plan or add your own. You can also encourage students to identify key issues in the preceding extract and devise their own questions or topics for discussion.

Antarctica

geophysics

ionosphere

meteorology

© 2025 Australian Academy of Science